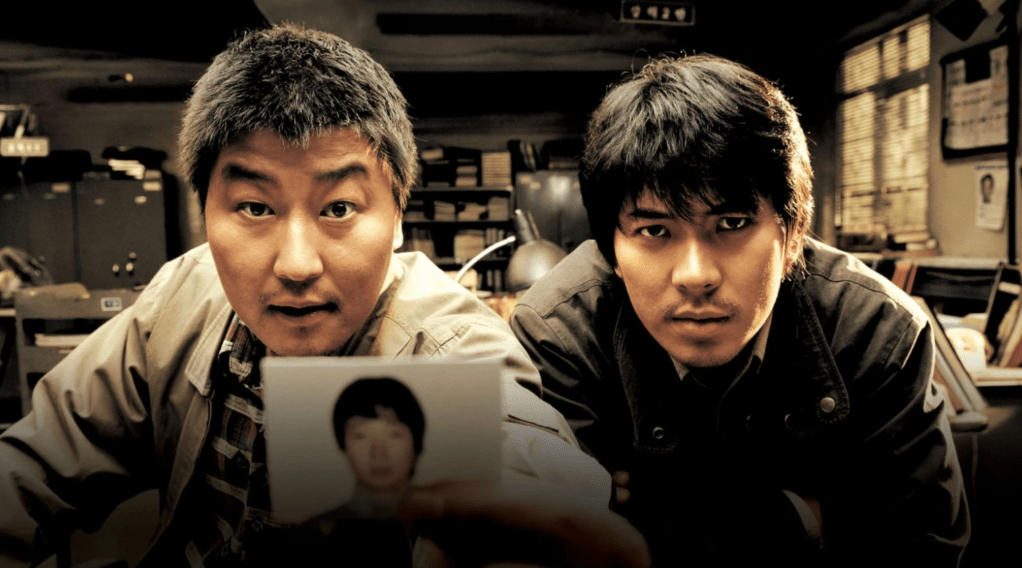

Det. Park Doo-man (Song Kang-ho) only needs to glance at a suspect once to determine their guilt. “One look and I know,” he brags in the excellent mystery thriller Memories of Murder (2003). But by this point in the movie we understand this as a misguided boast. Like all his colleagues in this small Korean town’s police department, Park is plainly out of his depth. He’s better at concocting resolutions than uncovering them; he’s an expert at finding people who seem plausibly liable for something heinous and then nudging them into falsely confessing. This is a method he and his partner, the more physically aggressive Cho Yong-koo (Kim Roi-ha), have employed for years now. This works dependably when the crime is both minor and a one-off in a town this small. “Be realistic, like in a movie,” Park blithely suggests to one suspect as his tape recorder, ravenous for an admission of guilt, beeps on.

But this technique will prove useless as applied to the crimes driving Memories of Murder. In this trope-shirking police procedural, set in 1986 and based on a real-life case, a serial killer emerges — and when a rapist-murderer with a distinct modus operandi is on the loose (he, or she, strikes only on rainy nights and preys on women donning red), hasty, more than likely to be inaccurate conclusions can’t cut it. A younger but more observant detective from Seoul, Seo Tae-yoon (Kim Sang-kyung), eventually comes to town to help. Initially his basic perceptiveness proves exceptionally — which is to say a bit depressingly, because it still feels rudimentary — useful. In one scene, Park and Cho only myopically notice that all the victims were beautiful and single; they can’t find anything else that would link them. Then, almost without missing a beat, Seo zeroes in on tinier recurring elements, like the rain, the red, and the radio song request that seems to always be asked for right before the killer strikes. Suddenly, the investigation seems like it’s getting somewhere. Seo is convinced shortly after arriving in town that he’ll only need two days and a couple squadrons of backup to find the culprit. But even his confidence and comparative shrewdness will only be so useful in a case this thorny, he’ll discover.

Memories of Murder at first seems to be a smart variant on the standard crime procedural — happy to hold up key genre elements but with visual style and frequently funny dialogue (that never undermines the situation’s seriousness) to give it a distinctiveness. We believe it will probably keep intact the genre’s penchant for letting things get slightly out of control but not so much that we suddenly stop believing in the ultimate efficacy of law enforcement; we believe there will be a satisfactory resolution for a time. But as strangled, tied-up corpses continue appearing — with any probable evidence washed away by the previous night’s rainstorm — the film progressively skews subversive, though never with didacticism or a heavy hand.

Though there are some memorable exceptions, the majority of crime procedurals depict formulaic fights against good and evil. In the popular Law and Order style, which endures as the most duplicated format, morality is cut-and-dried; you never question which side you’re supposed to be on. Although a cop character may be emotionally tortured — something which can lead to dubious on-the-job behavior and torrid personal lives — it is often characterized as excusable, maybe even something that makes them better at what they do because this line of work is so hard. (It shows commitment, too.) Memories of Murder isn’t unsympathetic to its main characters. Though not outrightly blundering, the men at its center are badly equipped for a case that requires a great deal more manpower and veteran-level expertise. And everyday mishaps are unavoidable. One crime scene is immediately destroyed when a tractor driver unwittingly smooths over any residual footprints. Huge, inattentive crowds tend to swarm around fresh bodies before cops can inspect, inevitably damaging evidence in the process. One evening, Seo tries to follow a suspect who has just boarded a bus only to find that his car engine has taken a rain check for the night.

Still, Memories of Murder doesn’t gloss over the corruption and cavalier violence that has indubitably ruined countless lives in its protagonists’ jurisdiction. When in an early scene Seo suggests to the police chief (Song Jae-ho) that the latest suspect — a disfigured, mentally handicapped young man — couldn’t possibly have committed the crimes because of his webbed fingers, the chief makes it loudly clear that he doesn’t care if this suspect isn’t responsible. How many innocents have been incarcerated because Park, Cho, and their associates have exercised this same callous carelessness? During one interrogation, a subject points out that in this town, even the children know that this force likes torturing innocent people. This department’s dingy, leaky basement has seen some shit.

Writer-director Bong Joon-ho, doing masterful work in what was surprisingly only his second feature film, assiduously avoids offering a familiar “one bad apple” argument. In Memories of Murder, which was re-released last year in the wake of Parasite’s astronomical international success, the rottenness endemic to policing isn’t let off the hook. It’s an unusual procedural in that it offers many of the characteristics that have helped make the genre endure without obscuring larger systemic problems. Bong’s canny reframing of certain expected conventions to evince bigger societal issues, would, with nearly 20 years of hindsight, become a clear trademark in his oeuvre. As noted by Collider’s Matt Goldberg, in Bong’s movies “it’s not as simple as ‘people are bad, so society is bad,’ but rather that we are so deeply flawed as individuals that the systems we create can only reflect those flaws.”

As evidenced by Memories of Murder’s hauntingly ambiguous ending, which is set nearly 20 years after the events that take up the bulk of the film, Bong isn’t a filmmaker who presumptuously claims to have answers. What makes him consistently great is that he knows how to make movies that are escapist but rigorous, stylish but grounded — as intent on entertaining as they are insistent that their audiences look at the world with a more discerning eye than they might have before. You never know what you’ll find.