We meet Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire), the lead of Agnès Varda’s terrific Vagabond (1985), for the first time in death. It’s a little after 10 a.m., and her frozen-solid body has been discovered at the bottom of a ditch by a farmer. An unseen narrator, whom Varda loans her voice for, roundaboutly tells us that the rest of the movie is going to be a portrait of Mona as she was seen by others. “Interviews” with a mixture of professional and cast-off-the-street actors recalling their time with this young woman tamper alinear scenes I suppose could correctly be categorized as speculative fiction. Vagabond comes to feel like a kind of mosaic — a scrapbook whose pages have been shuffled.

Though she never goes over her history in painstaking detail, we piece together through shards who Mona was before her premature death. In her late teens or early 20s, she once worked as a secretary. But, fed up with serving a boss’ needs and maintaining a living, and apparently with no family or friends she felt inclined to stay close with, she decided essentially to “drop out” of life in pursuit of her own kind of freedom. Stubbornly homeless, she now travels around France with no ideas about what she wants or where she ultimately wants to go. She hitches rides and agrees to go wherever the driver will take her. She gets odd jobs here and there to afford the occasional sandwich or baguette to sustain herself a while longer. (It isn’t uncommon, though, for her to pick a song on a jukebox to dance to over a meal.) It’s a wobbly, dicey way to live. But you sense her true appreciation of the extended exhale coming from being entirely free of obligation, no shackling routines or professional commitments to take up your days and, in the long haul, your life.

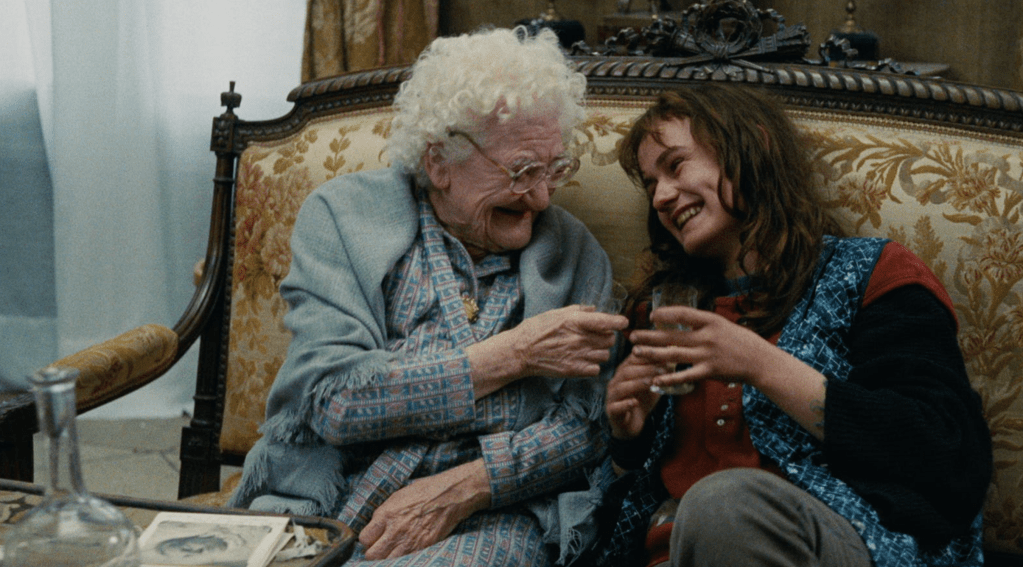

Marthe Jarnais and Sandrine Bonnaire in Vagabond.

But as it’s approached by Mona, true freedom is still hard to come by. There still arrive days where the priority becomes making a little bit of money. On others, she might be forced to fend off the kind of sudden danger that can come when you’re a woman traveling solo. One of the many things giving Vagabond its eerie quality is its reminders how constraining it is to live under capitalism but how much deadlier it is to reject it completely. It’s as much of a political statement as an oblique death wish.

Though I’d be interested in seeing a linear version of Vagabond seen through Mona’s roaring eyes and not those of others, Varda’s decision to splatter-portraitize her through secondhand accounts adds an intriguing dimension. Many talk of her as a personification of things they want but don’t, and probably will never, have: liberation from domesticity; what appears to be a complete lack of self-consciousness. Some think of her as apathetic and unnecessarily gruff; others are simply touched by her and her determination, from a rich old woman (Marthe Jarnias) with whom she shares drinks and laughs one afternoon to a middle-aged academic (Macha Méril) who briefly takes Mona under her wing.

In scenes where Mona briefly retreats from the loneliness of the road for meaningful interaction, Vagabond feels most optimistic. The only reliable thing about our legacy, Varda tacitly seems to say, is our impact on other people. Life is bearable not necessarily because of freedom, ultimately (it’s high on the list, though), and more the enriching connections we make when we’re alive. The movie has a feeling of transience, of forward movement; a frequently used stylistic device where Varda plants her camera somewhere and then keeps it moving, whether the character is in the frame or not (it’s like it were sitting on a conveyor belt), both conjures the cruel indifference of time but the power even a fleeting connection within it can take. You have to seize them while they still can be.

Sandrine Bonnaire and Macha Méril in Vagabond.

Bonnaire was only 17 and a half when filming began, and had only a handful of (albeit promising) credits to her name. Her work in Vagabond suggests someone far older, more hardened — embittered by years of frustration rather than just a brief, unimpressed taste of it. We can never truly know Mona: not too much unlike the people recalling her, we only have an impression made up of other impressions. Because this fierce character is drawn from a variety of perspectives, swinging from compassionate to contemptful, you can see the trickiness presented for an actor. How do you seem like an amalgam of other people’s stories while maintaining a humane through line that still feels plausible, legible, to viewers?

Bonnaire’s performance impressively never feels affected or self-conscious; she really does feel taken over by this young woman with dirty hands and matted hair and canned-good remnants drying on her lips, driven less by a love for her life and more a dogged determination to continue living it on her own terms. Her death — a result of bad luck, sheer unpreparedness for the cruelties of a winter outdoors — is unceremonious. But the mark she makes on the viewer, and on the people she met who’d never again know someone quite like her, persists.